I was reading a recent article in the National Post written by Barbara Kay called Send your kid to school by himself, and came across the term “physical literacy” for the first time:

There is a natural temporal window in which children learn to manage their inner fears by making decisions that combine the pleasure in taking a small risk with prudent self-protection. Call it a form of literacy: Just as hand-eye coordination, a form of physical literacy, must be learned by a specific age or it never comes naturally, taking age-appropriate risks in childhood confers greater adult confidence than a no-risk childhood.

I remembered a day after my first child was born, when a parent of older children asked me, “How is your child going to learn to walk if you keep catching him when he falls?” Many parents hover over their young children, as I was, but the process of feeling unsteady, and correcting that, is what teaches us balance.

I’m glad I was asked that question because, as I learned more about child development and worked with parents to teach their children to be more physically confident, I discovered many of those well-intentioned parents were doing some things that actually hampered this physical literacy.

Parents need to find their own balance between preventing injury and allowing their children space to grow physical abilities. Even if we are within arm’s reach of our children, they might still get hurt. Stressing about the possibility of falling isn’t helpful.

Here are seven ways we can improve our young child’s physical confidence:

Bonk-proof your house while your child is learning to walk.

Get rid of sharp-cornered furniture and remove or anchor shelving. Create a space where your child can attempt to get up, and has room to fall down, without the chance of banging his forehead on something hard on the way down.

Allow your child to test his physical boundaries.

Little ones do not usually break bones from falling from a standing position (although it is possible). Stand back from your child when he is moving around the room on his own and let him get back up on his own.

Give your child space at the playground to feel the different sensations that come from exploring on his own.

I like to observe parents when I’m at the park with my kiddos. I have noticed that mothers of three or four children will often relax on the bench with a coffee or visit with friends, while moms of one or two children will stand a foot or two away, ready to catch their children. When you watch the children whose moms are keeping tabs on them from the bench, you can see them focusing on their own movements. I notice that the children of moms nearby are focused on where their parent is.

Don’t rescue your stranded child immediately.

If your child has gone too far up the climbing structure and shrieks, “MOM! I’m stuck… HELP!!” Slowly and calmly stroll over to your child. Take time to get him thinking rationally and out of the freak-out part of his mind by trying to talk him down.

For example, you can try things like, “Well, I see a bar just below your foot so you can lower your foot until you feel it—I’ll watch to make sure that leg is going in the right spot.” When the child finds the bar, say something like, “Great! You did it—I’ll watch how you find the way down. I’m curious which route you’ll pick.” This kind of talking puts the focus on the child finding his own solutions and not relying on you to save him.

Use language that draws attention to what your child CAN do—encourage a feeling of capability.

Instead of saying things like, “Don’t do that—you’ll get hurt!” or “That’s too fast! Careful!!” be specific and neutral with your language. Try statements like, “What will happen if your tires slip out from under you—how can you keep your bike from tipping over?” This way of speaking gets the child focused on problem solving and thinking ahead.

The goal is to speak to your child in a way that makes him feel that he is either able to handle his body or will know what to do if there is a fall.

Make light of spills and minor falls.

Tipping over, falling down and banging our knees is normal when we are learning a new skill. When your screaming child runs toward you after falling, calmly ask something like this, “Was this a big fall or a little one?” Wait for his response then look for evidence of serious injury. If everything is okay, smile and try this, “Looks like you had a bonk—what were you learning to do?” (This complements the child for trying) I also like to say, “What do you need before going back to play?” (“Getting back on the horse” thinking) Often my boys will say, “Just a hug, Mommy.”

Give your child safe opportunities to test his new physical awareness.

As my two sons and I were biking home from school, my older one asked if he could go ahead on his own. I asked him this, “What you do need to remember to do that safely?” He told me about stopping and looking both ways at the streets, riding close to the side of the road, how to go around a parked car, and even what he’d do when he got home. Even though I was very nervous, I said, “It sounds like you know what you need to do to be safe. Go ahead.” I could feel my heart pounding as he rode away from me, but I knew I needed to let him do that.

Ask your child questions like the one I did to determine if your child knows what he needs to do, and what to do if he runs into trouble. If it sounds like he has covered the angles, let him go. (And breathe!)

I invite you over to my facebook page where I post free parenting resources to help you raise happy, confident children.

I believe that being able to calm ourselves in the throes of emotional intensity is one of the most valuable parenting skills to develop.

The wild behaviour that can happen when our rage hijacks us can seriously damage the relationship with our children, grow negative core beliefs in their minds, and inadvertently teach our kids to react in the same manner when they, too, get taken over by big feelings. If you haven’t heard of the term negative core beliefs before, stay tuned, because I’ll be writing about that in the future.

To create a calm-down plan that actually works, some understanding of the dynamics in play is necessary, as it is a combination of our self-talk, negative core beliefs, exhaustion level, and pure brain reactions that create that intense rushing sensation to shout or hit that can be very hard to stop.

Here are the elements of a successful calm-down plan:

What self-talk messages are your core beliefs shouting out? I don’t have time for this sh*t! If this child doesn’t stop yelling, I’m going to lose it! This kid is going to be the end of me. I’m too tired for this!

This kind of self-talk is often to blame for revving us up and making calming down hard. I wrote about the positive and negative messages we can tell ourselves and how they affect our frustration here. It is our self-talk that influences whether we see the world as our oyster or as something out to get us. It can shout statements of intolerance or whisper messages of reassurance and capability.

Controlling this self-talk is the first step to successfully calming down. Take a moment to “see” your thoughts—to be aware of the harsh messages. There is usually a pattern to your inner voice, which provides a glimpse into the workings of your subconscious. Writing your self-talk messages out in a journal is really helpful for identifying the core belief messages held in your subconscious that might be tripping you up.

When you find a negative self-talk message, ask yourself if you want to believe it or hear it. If the answer is, “no,” ask yourself what you’d like to believe instead—this would be the corresponding positive self-talk message. I encourage you to write them down so you can practice remembering them when your mind goes into flip-out mode.

I call that thought awareness and correction, which I wrote about here.

You will be more able to hear your positive self-talk and have empathy for others when they are melting down if you are not exhausted. Determine what is zapping your energy tank and take steps to change that. Do you need to: Schedule in rest time? Find other people to take care of your children for a few hours? Delegate parts of your to-do list? Spend less time thinking negatively? Attempt less?

There’s a part of our brain, the reptilian brain, which is hard-wired to keep us safe. This part kicks into gear when there is a real or perceived threat. It ramps up our heart rate, breathing rate and tenses muscles to get us ready to jump—called our “fight-or-flight” response. The focus suddenly switches from thinking calmly (being rational) to a purely physical reaction. This part of your mind is basically shouting, “DEFEND yourself!”

Once that happens, the connection to our calm, rational brain gets shut down. This is why someone who is flipping out has a very hard time hearing good logic. The priority needs to be to get back in the rational mind! When you are in an argument with someone else, taking time to make the switch back to thinking rather than defending will make the disagreement more productive.

The thing is, much of the time, the perceived threat that flips the switch on this response is a result of our self-talk (which is why I put that point first). We can actually activate this response with our thinking—we can think our way into panic in cases where a real threat isn’t there.

For example, if a mom tells herself, Oh Nooooo! I’m going to be late—argghhh! This is brutal… I need these kids to stop shouting NOW! He just WON’T LISTEN! and starts ripping around to gather things and get out the door, she may actually activate her reptilian brain. This will make it very hard for her to think calmly for a way to soothe her tantruming child, and be clear about what can be done that is helpful.

The rush of adrenaline is often the culprit that makes us shout, throw, or say things before we even have a chance to consider what our own body is doing.

The best way to reel in this physical response is with big, long breaths, but you have to remember to take them! Slow, mindful breathing is a fabulous way to stop the reptilian brain and get the flow back into your rational mind.

Include ways you will be able to do the following:

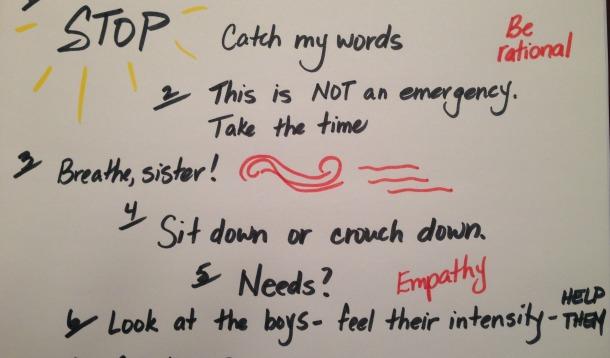

1. Hit the pause button—STOP talking. “Catch your mean words, harsh tone or hits before they come out.” (You can use that statement with your kids, too)

2. Identify your negative self-talk messages.

3. Create positive ones to believe instead.

4. Talk yourself down.

5. Take long, slow breaths (change where you are if that helps—sit down or crouch on the ground)

6. Ask yourself, “What do I need right now?” (A break? To try again? Help? Food? A walk? To speak up?)

7. Then ask, “What do my children need?” (Support? Empathy?)

8. Take action to de-escalate. What is the first thing to put your focus on?

When you are making your plan, just include the points above that you need. When you look at mine in the photo above, you can see I used some keywords, colours, and questions that I find helpful to pulling myself from my irrational to rational mind.

I know calming big, intense emotions can be hard. Please be patient with yourself as it may take time to see consistent results from your plan—keep practicing and identifying better methods for you when your reptilian brain takes over. I continually post free parenting resources on my Facebook page, and invite you over there to learn more and ask questions.

One of the most common requests I get from parents is, “I’ve tried everything and my child still won’t listen. What can I do?” There are several factors involved in a child’s willingness to cooperate. A child not doing what she is told is less about “not listening” and more about how able she feels to do what you want her to. Before getting frustrated, try asking yourself the following?

How full is her attachment tank?

When I hear this, the first thing I do is determine how full or empty that child’s connection (or “attachment”) tank is with her parents. Children will feel more inclined to cooperate when they feel securely attached to the person delivering the instructions. I explain more about how to fill the tank here.

Is she compromised?

The next thing is to check that kid-compromisers are not too high, as these also make it very hard for children to hear and want to follow your instructions. Kid-compromisers are anything that put a child’s focus on getting their physical needs met, and thus not on you. If a child (and adult) is preoccupied on eating, sleeping, or regrouping due to feeling hungry, tired, or over-stimulated, he is extremely unlike to be able to listen to you.

Do you have unreasonable expectations?

Sometimes very well-meaning parents ask too much of their children for their age and physical abilities. One parent shared her intense frustration with taking her young son to the grocery store and struggling to keep him from racing around, grabbing things on the shelves, and begging for junk food. I asked her, “Is it possible to get groceries without him?” She said it was, so I encouraged her to pick her battles and just try again in a few months. In the meantime, I asked her to train him how to be in a grocery store, and what would happen if he wasn’t able to do what she needed.

Another easy fix is to decrease temptation by childproofing your home to a degree that your child can be in areas without you needing to constantly say, “No. Don’t touch that,” or “Don’t open that drawer.”

Is she dealing with intense emotions?

It is normal to have big, strong feelings on a regular basis. I know big reactions can come at inopportune times (like trying to get out the door) but when time is taken to calm everyone down and regroup, kids will be more able to hear you. I’m going to be writing more about having a calm-down plan in my next post!

Meet the emotional intensity with empathy. Reel in your negative self-talk like “I don’t have time for this crap!” and look at your emotional child. Connect with her by asking yourself, “What does my child need right now?” I know you might have a need to get somewhere or do something, but these emotional outbursts tend to decrease or settle when a child feels important to her parent and sees a parent using a calm-down plan (and is taught how to have one, too.) If you are having a tough time being empathetic, as I certainly have some days, I wrote this article to address that feeling.

Was she surprised?

Children need to know ahead of time when a transition is coming. Use signals and warnings to avoid surprising a child with an, “Okay, time to go home.” Here is an example of a morning routine to reduce surprises and increase cooperation.

Are you using clear instructions?

Use simple, clear instructions to deliver your message. Remember to use a statement like, “It’s shoes-on time,” versus a yes/no question (which will likely be met with “NO!”). Oh, and don’t throw an, “OKAY?” at the end of an instruction—that turns it into a yes/ no question.

Are you being friendly?

You don’t need to be coercive to get kids to do what you want. Be friendly, be fun, be caring, and smile. Find a way to deliver your message in a firm and friendly way. Do you like to be nagged at or continually told what to do?

Here are examples of ways to communicate that encourage cooperation:

Instead of, “Go wash your hands.” Use: “Everyone with clean hands is eating.” (smile)

Instead of, “I told you three times already to get your shoes on!” Use: “When this song is over, you know it’s time to put your shoes on.” (Use of a transition signal and a when/ then)

I continually post tips like these, awesome articles by colleagues, and questions for parents on my facebook page. I’d love to see you and hear from you over there.