When my daughter was five years-old, we took a trip to Chinatown in Toronto. The streetcar was heaving that day, bodies crammed in together, and one woman kindly gave up her seat so my daughter could sit down. As more people piled onto the streetcar, I was pushed forward by the crowds, further and further away from her. I could still see her, though, and I gave her plenty of reassuring smiles so she knew that everything was okay.

We arrived at the subway, all doors opened and the crowded surged out. I stood my ground, looking back at my daughter and indicating she should stay exactly where she was until I could get back to her.

It was when the streetcar was almost empty that it happened. A man grabbed my daughter and hauled her to her feet. “Driver! Hey!” he yelled. “Someone's left this little girl!”

The driver turned. My daughter squirmed in his arms, clearly panicked.

“No,” I called, rushing forward. “This is my daughter. I'm her mom.”

The man looked at me, then at my little one, uncomprehending. Disbelieving. You see, my daughter and I look nothing alike. I am of European descent, and she was adopted from China at nine months old. He glanced over at the driver again, as if asked for an explanation. His big arms were wrapped tightly around my child. I felt a stab of terror. What if he would refuse to believe I was her mom? What if he wouldn't give her back?

Then, he made a decision.

“My mistake,” he said. He put my daughter down and she leaped into my arms with a cry.

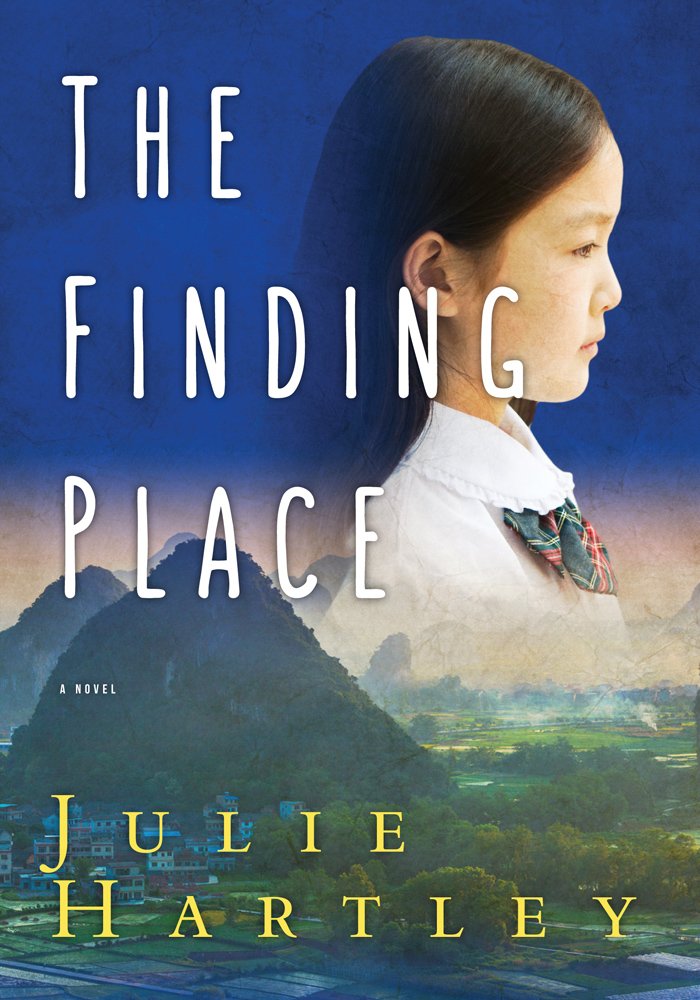

This incident made such an impact upon me that it made it into my novel for children, The Finding Place, which deals with the experiences of a fictional adoptive family. The man's reaction was well meaning – he thought was helping a child who had been left on the streetcar by her Chinese family. But it was also born of ignorance, and the belief that all families are made up of people who look alike. Most mothers of transracially adopted children will have had similar experiences: inappropriate and rude comments that arise from misconceptions and ignorance.

“How much did you pay for her?”

Yes. I was actually asked this. By a doctor, in hospital, during an internal examination. While examining me, he had asked whether I'd recently become a mom – to which I had replied, naively, that I had. Realizing he was asking me a medical question, I'd added that my daughter wasn't the result of a pregnancy, she was adopted from China. I was astounded by his response. Not just by how ignorant (and totally erroneous) the statement was, but also by the fact that it was personal, rude, and invasive.

Inappropriate questions and comments often come from children, and while I would never blame a child for their curiosity, and do blame parents for failing to step in when that curiosity is misplaced. Many times, it has seemed to me that the only reason a parent does not step in is because the child is verbalizing something they would also like to know. “Is that your daughter because she doesn't look anything like you,” one small boy shouted at us in the lineup at a grocery store one day. The boy repeated his question, louder each time, while mom flicked her eyes over the top of a magazine, inadvertently catching mine. I usually shy away from conflict, but I'm also protective of my daughter, who was confused by the unwanted attention. “Perhaps you should ask your mom whether it's okay to ask personal questions of complete strangers,” I told him gently. The mom's eyes darted back to her magazine.

Over the years, not all the questions we've faced have been rude. Some have been downright funny. When my daughter was about six years-old, her friend – a smart and feisty little girl - came over to play. She started to ask me about adoption. I changed the subject, aware my daughter was listening. But the questions continued. Finally, when my daughter ran upstairs to fetch a toy, I sighed. “Okay,” I said. “Ask me your questions now.”

“Is it easy to do an adoption?” the little girl asked.

I was confused. “Why?” I asked. “Why do you want to know that?”

“Because my mom just had a baby and I'm sick of him,” she said. “I want to get him adopted.”

Many of the comments people make are a result of racial stereotypes, and a mistaken sense that stereotypes are okay if they are not obviously negative. “She's so tall for a Chinese person.” We've had that many times. “How come her hair is brown, not black?” And one of my favourites: “I bet she's great at music and math.”

Demystifying transracial adoption was one of my goals when I wrote The Finding Place, a novel for 9-14 year olds. My book is a coming-of-age story written from the perspective of an international adoptee who struggles with many of the same challenges all teens face: discovering her identity, relating to parents, coming to terms with divorce. Internationally adopted kids often have a tougher time with life's challenges because they have already faced abandonment, they have already lost their birth culture, and a part of their identity remains a mystery to them. In writing my book, I wanted to give adoptees a chance to see their own experiences directly reflected in a novel – something they rarely experience. But I also wanted to send a clear message to all readers. Not all children look like their parents. Not all children are raised by their biological parents. Our differences set us apart, but they also unite us. Families are families, no matter how they are formed.

Julie Hartley is the author of The Finding Place, a novel for 9-14 year olds published by Red Deer Press in September 2015. The novel is available online through Amazon.ca, and in stores. You can read more about Hartley's story at www.juliehartley.ca