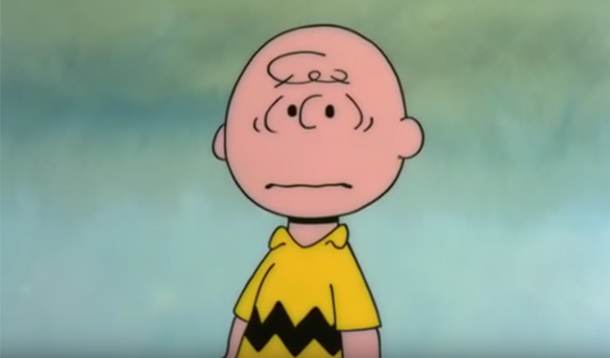

My nine-year-old is Charlie Brown, basically. Lately everything is either "stupid" or "boring" (to him) and "exasperating" (to me). Time and again, studies have shown that having a negative outlook is bad for both physical and mental health.

Are “Negative Nellies” and “Debby Downers” born or made? A bit of both, it seems. To some extent, having a positive outlook is something I have to work at. Since I’m not exactly a natural optimist myself, I worry about my son falling into the same mental health trap. So, I’ve been trying to reform his pessimistic attitude before it’s set in stone.

As a longtime fan of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), I wondered whether this approach could also work on children—the idea being that by changing our thought patterns, we can also change how we act and feel. Kids are told to imagine there is a “bully in their brains” feeding them unhelpful or damaging thoughts. For children like my son, who experience high levels of anxiety, the concept of a bully distances them from their own (bad) thoughts, and empowers them to challenge or ignore what the bully says.

Whenever I notice the bully hijacking my son’s brain—saying things like “I suck at this,” “I will fail” or, my personal favourite, “My life is ruined”—I call him on it. Brain bullies have a tendency to exaggerate and generalize. The words “always” and “never” are red flags, as are “what if” statements since they tend to generate undue worry. The best way to confront a brain bully is by asking factual and logistical questions. Is your life actually “ruined” or are you just bummed because something annoying happened? What is the probability of this awful thing happening? How many times has it happened in the past? Such questions are usually enough to squash the bully in his tracks. But I will offer some alternative thoughts: It’s not the end of the world, even though it feels like it. Tomorrow is a new day, and good things will happen in the future.

With time and practice, my son started to come up with his own comebacks. When his brain bully shows up unannounced and says he can’t “get the stupid computer to work,” I can offer up ideas if he gets stuck. “I just have to be patient and wait a while” or “I can always ask for help.” Although I do my best to model optimistic thinking, sometimes I fall prey, and my son loves giving my brain bully what for.

His new favourite game is called “Situations” where one of us will describe a (potentially worrisome) situation, and the other will come up with possible outcomes. Brainstorming before my son even finds himself in that predicament defuses the stress and anxiety. And he’s far less likely to view those situations in a negative light because he knows what he can do if it ever happens.

Gratitude is also a nice way to end the day for glass half-empty people. And bedtime is a good time for reflection and relaxation. So, while I’m tucking him in, I like to ask my son about some good things that happened during his day, or things in his life for which he is thankful. The silver lining is there, even on the worst days, even when it doesn’t feel like that way. Cynics like my son (and I) simply have to dig a bit deeper to find it.