Imagine having your school-aged son taken from your home and sent hundreds of miles away to a boarding school where your worst nightmares of how he might be treated actually happen? This unthinkable event was reality for the Wenjack family and the parents of 163,000 Canadian children who were taken from their families and send to residential schools 50 to 60 years ago.

The story of how Chanie Wenjack, at age 12, was forced to go to a residential school 400 miles away, later dying after escaping and attempting to walk back home along a railway track, is being brought to our attention by Gord Downie and his Secret Path project.

I knew that when I planned to see Gord Downie’s Secret Path show in Toronto, there would be sadness and tears. I wanted to go, knowing what I might be walking into, because standing in the space of Gord, the musicians, the Secret Path film, the Wenjack family, and other Indigenous people was a difficultly important thing to do.

This sense of importance comes from my personal connection with Gord, the connection I feel with Indigenous people, and a deep desire to participate in the truth and reconciliation process. Growing up in Thompson, Manitoba, and later having my first teaching jobs in First Nations communities and isolated reserves, I learned to appreciate and love the Indigenous people and culture.

I had the opportunity to live on a remote reserve for a year and experience both the pain and beauty of being there. I remember one family in particular – the father’s loyalty to his family was so inspiring. He did everything he could to financially, emotionally, and spiritually support his children while trying to keep them away from addictive temptations.

While up in the North, I heard stories first-hand from those who had been in residential schools, and felt those years ago, mortified that people would willingly harm others – children, in particular. Where were their hearts when they took those children hundreds of miles away from their families?

When the first scenes of the Secret Path film were lit up on the big screen at the back of the stage where Gord and the musicians stood, I was struck by the image depicted of Chanie Wenjack. My own boys look a lot like him: they have dark eyes, dark hair, and a dark complexion (my husband’s family is from India). I kept thinking about my own sons being taken out of my house to a place far away where I couldn’t see, hear, or hold them. It was an unbearable thought.

At the end of the performance, the Wenjack family members were invited up onto the stage. Pearl (Wenjack) Achneepineskum, the sister of Chanie Wenjack, sang a beautifully haunting song, then said: “To all of you in the audience. Be thankful your children are only seconds away.”

Earlier in that evening, while we waited in a long line to pick up the tickets, those around us in that space doing the same thing were some of the most influential people in Canada. Some of those people were Marc and Craig Kielburger (co-founders of WE.org), David Zimmer (ON Minister of Indigenous Affairs), Michael Budman (ROOTS), Atom Egoyan (Film Director), Joseph Boyden (Author), Paul Langlois (The Tragically Hip), and Chief Stacey Laforme of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

Most of these people were at the show with their family members, which seemed to be an over-arching theme of the event and even the Secret Path movement: families connecting to heal the past and create a brighter future together. The families at that show have the ability to positively influence the relationship and truth and reconciliation process for Canada.

I was there with my dear friend Erica Ehm, founder of YMC, who said, “I kept thinking of the words of Sting’s song ‘Russians:’ Russians love their children, too. It’s a universal truth – we all love our children. This really is about families.”

Gord Downie’s two brothers Mike and Patrick were on the stage with him after the performance. Mike was the emcee for the evening. I watched Pearl Achneepineskum stand on the stage near them, openly weeping about the brother she lost fifty years ago. She stood for a few moments with tears streaming and I watched Gord looking at her. He moved towards her, holding her in a long embrace. We all just got quiet and felt that.

Pearl’s vulnerability and strong emotions even though this happened fifty years ago remind us that this is real. One group of people took another group’s children away. That’s what happened. This experience turned the words I have read in articles and heard on the news about residential schools into feelings deep in my heart.

At the end of the show, Gord said: “Let’s not celebrate the last 150 years. Let’s just start celebrating the next 150 years. Just leave it alone.”

The cover photo of the Downie Wenjack Fund Facebook page has a picture of the Downie family and the Wenjack family with the simple words: “Do Something.” Maybe that something starts with Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians being in the same space together?

Perhaps part of my “do something” is to connect with an First Nations community near us or with those I used to work with? I’m certainly going to share my experience at the show and the curriculum being developed by the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund with the students in my school.

Discussions with today’s youth about this historically significant period of time are important to making concrete changes for Canada as our young people grow older. These talks will help shape the future of our country into a place they are proud to call home.

My bigger goal for doing something is to talk with the people I met at the Secret Path show about a system of education I believe might work in remote reserves so the children there wouldn’t need to leave their homes.

Pearl’s shared these words in a recent CBC article:

"I'm very much concerned about the children going to high schools and losing their lives," said Achneepineskum, a grandmother to dozens of school-aged grandchildren. "Every time a child loses his life or her life, I walk through the same path and I remember the fear and the unhappiness of going, and wanting to get home."

Maybe there is something I can do to change that? I’m certainly going to try.

I encourage you to see the Secret Path film, buy the book, and hear the music. It might be a tough and uncomfortable thing to do, but often uncomfortable is the gateway to positive change.

Early in Friday’s show after we all applauded at the end of a song, Gord looked out at all of us and said, “It’s going to get harder to do that as the night goes on.” That’s okay, Gord, we stayed with you, applauding who you are and the deep emotions you are stirring in us. We can do “hard.”

One of the most painful things to hear our children or students say is: “I’m stupid” or “I’m dumb.” Our first reaction might be to utter something to counter their statement like, “No, you’re not!” but that response may actually not be helpful. Using phrases that show our children how to address their negative core belief thinking and change it will grow their self-confidence and motivation to handle any tough stuff that arises.

To know better how to respond to “I’m stupid” in a supportive way, it’s good to understand where this thinking comes from.

You may have heard of Carol Dweck’s work regarding something called “mindsets.” In her words: “For twenty years, my research has shown that the view you adopt of yourself profoundly affects the way you lead your life.”

Dweck believes the views we have of ourselves fit into two general categories: fixed and growth mindsets. She says that these mindsets are the opinion we have of our qualities and characteristics, where they have come from, and whether these are able to change. The fixed mindset comes from the belief that your qualities are not changeable – you are who you are. A growth mindset is derived from the belief that your basic qualities are things that can be changed through some effort.

If you have been following my writing, you have likely heard me mention the term: negative and positive core beliefs. These beliefs support or detract from the mindsets we have of ourselves, others, and the world around us. Core beliefs are the messages we tell ourselves based on the experiences we have. How much we believe these messages depends on the supports around us and how much reinforcement we get that further solidifies a particular message.

I’ll use an example to explain. Consider the situation where a child tries some math at home, doesn’t understand it, and gets it wrong. If she cries, saying, “I don’t get this! Math sucks,” and is met with this reaction from a parent: “I don’t blame you, I didn’t get math either. I guess you’re just like me,” she might start to believe that being bad at math is just her lot in life. If she continually hears this kind of message, she might just throw her hands up and expect math to suck her whole life. The negative core belief of I’m not capable to do math or I’m not smart enough to do math might grow and stick with her.

There’s a saying attributed to Henry Ford: “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t, you’re right.”

The “I’m stupid” words might be coming from a negative core belief that has grown as a result of some experience regarding learning in the past but it can also be simply a child-view of overwhelming frustration.

Our job as parents is to help children be aware of the idea that our minds and our thinking can really change how successful we are, to promote the growth of positive core beliefs, and foster the development of a growth mindset.

How do we do that? Try these:

In order to support our children and students to address this kind of thinking, the first step is to focus on the idea that her words are a reaction to a situation, not a trait she has. It’s not about being smart or not smart: it’s about facing a challenge and feeling frustrated.

Try language like this: “Did you know that most of us have trouble with words sometimes. That’s pretty normal – I even get stuck on some words when I read.”

Or this: “I see that you are frustrated because the word you’re reading is new to you.”

Avoid saying this: “You’re not dumb. You’re smart – look at how many words you did get right.” We don’t want to argue with them about how smart they are: we want to demonstrate that what they said is a reaction to frustration, not who they are.

Dr Dan Siegel’s mantra of, “Name it to tame it” works beautifully in this situation. Putting words to our child’s feelings help them to process those and move on. Use specific feelings words to describe what you see your child going through.

“It looks like you feel embarrassed when you don’t know how to say a word. Is that right?”

And, “Reading can be really tough sometimes, can’t it. Do I see you feeling frustrated about that?”

These words can really trigger us, particularly if we’ve ever thought them ourselves. We also can feel emotional when we hear statements like this because we don’t want our children to feel so badly. Please do remember to reel in your reaction and stay calm and cool.

Respond immediately, providing clear and consistent feedback to counter the comment.

If your child comes home saying, “I’m stupid” but you don’t really know why he or she is saying that, remind yourself that the context is important. Put your detective hat on and try to learn as much as you can about the situation that prompted the comment. Once your child feels safe and relaxed enough to share that with you, calmly go back to the first three steps of addressing the remark.

Show your child that it’s okay to experience challenges. I often say things like: “That was tricky, but that’s okay, we can do ‘tricky’.”

Also, questions like: “If you want to get better at this, what do you need to do?” help show children that practice, making mistakes, and going through rough patches are quite normal and even expected.

I also like this question: “I love trying new things even if I make mistakes. Can you think of why I’d say that?”

These kinds of questions can help your child see that he or she is in a process of learning and it doesn’t happen in one burst. This will also show your child that there aren’t specific labels to define her. Challenges can make us better at things!

If you would like more information about Core beliefs, please look at the first section of my eBook called Taming Tantrums: A Connect Four Approach to Raising Cooperative Toddlers. I know this book has toddlers in the title, but the first section on core beliefs is for parents with children of any age. I also recommend looking at my app also called Taming Tantrums (search for it in your smartphone app store), for more examples of phrases to help grow positive core beliefs. Do you have any questions? Feel free to ask those over on my Facebook page.

![]() RELATED: Does Your Child's Teacher Use Punishment? Here's What to Do...

RELATED: Does Your Child's Teacher Use Punishment? Here's What to Do...

I think back to the days when I was a teacher before becoming a parent, which was about twenty years ago. Standing amidst 25 to sometimes 35 students, there were many moments where I just couldn’t think of how to make a student do something he or she was refusing to do.

I admit that sometimes I resorted to punishment rather than positive discipline and all these years later I cringe at those thoughts, wishing I could go back in time to change things. I now have better perspective into the potentially negative effects of that punishment.

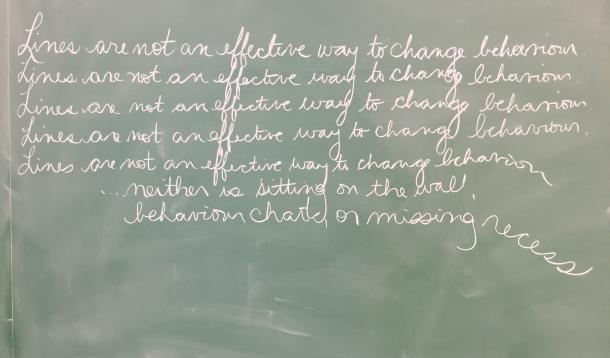

Today I opened my Facebook profile to learn that a twelve-year-old boy was told to stay in to miss recess in order to write lines because the lines he was instructed to write last week in his binder (for not finishing his homework) didn’t make it to school that day.

I’m trying to write this post from a neutral perspective but I’m going to be honest and let you know that I’m livid. I’m upset because lines are being used as a punishment, that recess was taken away, but more so that this student is going to have to work hard to continue to love learning.

As I’ve walked through the halls of some schools recently, I’ve seen children being told to “stay on the wall” (sit against a wall during recess for a prescribed time – in a place they can be seen by the other students), doing lines, shouted at, and told that if they made any sounds, their art time was going to be taken away. I’ve even heard of teachers throwing desks at students and shaming them in front of the whole class.

I have a great deal of respect for teachers, and value their impact on our young people. My goal is not to be negative towards teachers in general but rather to address the use of punishment in schools.

One of the important tenants of the school I started this year is that our adults will not use punishment, shaming, belittling, or any other negative means when interacting with students or each other.

I asked the students in our school to share experiences they’ve had in different schools they’ve been to in the past. This is what they had to say when I asked, “Did any of the teachers in your old school take away recess when you did something wrong?”

Three of them said, “yes.” I then asked them to tell me about why their recess was taken away. One said he kicked a ball that mistakenly hit another boy in the face. The teacher told him he had to miss the next recess as a result. He also mentioned that he’d lose recess or have to sit against the wall for doing something he wasn’t supposed to.

I asked him: “Did it make you not do that again?”

He looked right at me and said, “Nope.”

He went on to say: “It’s not effective because every single kid who got ‘put on the wall’ still did the same thing every day. I don’t understand why the teachers kept getting them to do that.”

Another student said, “The punishment had nothing to do with what happened! It didn’t make sense.”

These boys are right! Punishments like these actually have a very small likelihood of changing further behaviour. Similar to what we know about punishments as they are related to parenting, methods that cause a child to go into their fight-or-flight part of their minds just get kids to be mad, preoccupied about defending themselves, and hating school.

Negative punishments also can cause a rift in the relationship with the teacher, which is a significant problem. It is well known that a positive relationship between a child and his or her teacher strongly influences how much that child likes school and learning.

In this article published by the American Psychological Association, the authors said:

“Picture a student who feels a strong personal connection to her teacher, talks with her teacher frequently, and receives more constructive guidance and praise rather than just criticism from her teacher. The student is likely to trust her teacher more, show more engagement in learning, behave better in class and achieve at higher levels academically. Positive teacher-student relationships draw students into the process of learning and promote their desire to learn (assuming that the content material of the class is engaging, age-appropriate and well matched to the student's skills).”

Two years ago, along with fellow psychotherapist Katie Hurley, we wrote about the practice of taking recess away. The point of our Huffington Post Education article “Let the Children Play! Especially During Recess” was to encourage teachers to stop using this practice.

When this post was first published, there were hundreds of comments on my Parenting Educator Facebook page from parents frustrated with the negative methods that teachers were using to correct their children. I also heard from many parents that they didn’t think it was their place to bring this up with teachers.

*I do believe that is it our place to address when negative punishment is used with our children.

The question is how to do this without undermining the teacher. In some cases, parents even need to be mindful to not make their child a target in the eyes of the teacher (I’ve seen this happen).

As with any situation between two people, I suggest speaking with the teacher first before going to the vice principal or principal.

I’m a big fan of relationship building so I suggest approaching that conversation mindfully: ask to book a time that suits the teacher come in with an approach of being on the same team. Don’t ambush the teacher at pickup time.

Open your conversation in a non-threatening way (we’re trying to keep the teacher out of a defensive state of mind). The challenge is to address the behaviour you don’t agree with while at the same time still communicating to the teacher that you believe he or she is a capable person.

Trying something like this: “My son told me that he has to do lines because he didn’t complete his homework. I’m here to learn more about that.”

If the teacher says something like, “That’s right. Your son was goofing off during class and didn’t get his homework done so he has to do lines,” try to get the teacher thinking of alternatives.

I suggest something like this: “Lines aren’t really going to work with my son so I was wondering if you’ll consider a different approach? After I spoke with him, I learned that he didn’t really know how to do the math. Could you please check to see if he’s having trouble first?”

Continue to offer suggestions that encourage the teacher to connect more with your child. If the teacher is open to this, see how the next few weeks go, but if the teacher blames your child or refuses to listen to you, it’s time to visit an administrator.

If you are looking for resources to take with you to a meeting with a teacher, administrator, or even coach, here are a couple I suggest:

Positive Discipline in the Classroom by Jane Nelsen, PhD

The Edutopia Facebook page

Katie Hurley, LCSW 's writing -- particularly for the Washington Post. Her most recent one there is: "The dark side of classroom behavior management charts"

My article which addresses how to reduce the stress of homework (we do not assign ANY homework in our school).

![]() RELATED: 7 Ways to Help Your Child Handle Their "After School Restraint Collapse"

RELATED: 7 Ways to Help Your Child Handle Their "After School Restraint Collapse"